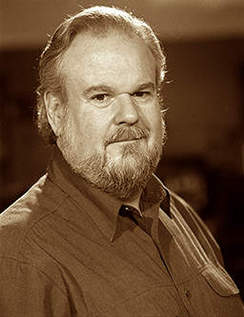

Scott Alarik has been the principal folk music writer for the Boston Globe since 1986. He is also a frequent contributor to Sing Out! the Folk Music Magazine, and was folk critic for the public radio program “Here and Now” for seven years. From 1991-97, he was editor and chief writer for the New England Folk Almanac.

Scott Alarik has been the principal folk music writer for the Boston Globe since 1986. He is also a frequent contributor to Sing Out! the Folk Music Magazine, and was folk critic for the public radio program “Here and Now” for seven years. From 1991-97, he was editor and chief writer for the New England Folk Almanac.

Pete Seeger calls Alarik one of the best writers in America,” and Dar Williams calls him “the finest folk writer in the country.” Irish Echo and Wall Street Journal critic Earle Hitchner says Alarik is “one of America’s most astute music critics and chroniclers.” Troy Record critic Don Wilcock wrote,For my money, Alarik is the best.

With the release of a new CD, “All That Is True,” and the launching of a long-awaited website, scottalarik.com, Alarik hopes to more closely connect his long careers as music journalist and folk singer.

The album was produced by brilliant young fiddler-pianist Hanneke Cassel, and features Boston’s hottest neotraditional performers, including Crooked Still’s singer Aoife O’Donovan, cellist Rushad Eggleston, and banjo prodigy Greg Liszt, who Bruce Springsteen asked to play banjo on his world tour honoring legendary banjo-player and folk singer Pete Seeger. Also on the album are mandolinist-guitarist-songwriter Jake Armerding, and superb Celtic-American fiddler Eric Merrill.

Alarik’s website features a large library of feature stories he’s written about folk’s storied past, vital present and promising future. “I see it as an ongoing version of my book, “Deep Community,” he says; “kind of a moveable feast of folk stories.”

Before moving to Boston in the early 80s, Alarik, a Minnesota native, spent nearly 15 years as a folk singer and songwriter. He released three albums and appeared regularly on the public radio hit A Prairie Home Companion. Host Garrison Keillor wrote of him, I have rarely seen an audience in such a good mood as when he’s just been there. The Boston Herald’s Daniel Gewertz called him simply “the complete folk entertainer…a rich-voiced balladeer and songwriter…and a droll comic between songs.”

Alarik headlined at most of the major folk venues of the ’70s and ’80s, including Caffe Lena, the Coffeehouse Extempore, Somebody Elses Troubles, Earl of Old Town, Godfrey Daniels, the Cherry Tree, the Folkway, Old Vienna, the Speakeasy, and Passim. He appeared at many major folk festivals, including Philadelphia, Winnipeg, Old Dominion, Minnesota, Toronto, and San Diego.

With his move to Boston, he began writing for a small folk magazine called the Black Sheep Review, drawing the attention of Boston Globe folk music and theater critic Jeff McLaughlin, who invited him to contribute as a freelancer to the newspaper. Within two years, McLaughlin had handed the folk beat to Alarik, who has covered it ever since. During that time, writing overshadowed performing for Alarik. In 1991, the Globe briefly minimized the attention it paid to folk music, and Alarik, in partnership with the Folk Arts Network, founded the New England Folk Almanac to fill the breach in print media coverage. From 1991-97, it grew from a regional music calendar into a nationally respected magazine. At the peak of its popularity in 1997, an internal struggle within the sponsoring organization forced Alarik to leave the Almanac. It went out of business a year later.

Alarik revived his performing career at that time, and was soon performing again at major New England venues such as Marbleheads fabled me & thee Coffeehouse, Joyful Noise, and Club Passim, as well as most of the vibrant community coffeehouses that dot the greater Boston landscape. In 2000, he released a CD called -30-, the name taken from an old newspaper symbol for end-of-story,” and noting his 30th year as a folk music professional.

Since its release, Alarik has performed at major festivals throughout the northeast, including the Philadelphia, Boston, and Champlain Valley folk festivals, and New Bedford Summerfest. In 2003, he hosted the Newport Folk Festival.

For me, Alarik told the Troy Record, when I went from being a folk singer to a music writer and back to being a folk singer again, I didn’t change jobs. I changed tools.

The job remains the same, whether drolly explaining the roots of a cowboy ballad he is about to sing, or singing the praises of the next big folk star in the Boston Globe. And that job is telling folk music’s story.